Issue #09:

The Equitable Wealth Equation

Wealth Building in Community Development

In a country based on the accrual of capital, wealth building aligns as closely with the American image as the Stars and Stripes. Yet the very notion of who builds that wealth, and who ultimately bears the cost of its accumulation is a story just as deeply woven into the fabric of the American story. In Issue 2, we highlighted the accounting of racialized expenses and revenues in community development, built on the foundation of the theft of land and labor and compounded through exclusionary access to investment and benefits and the active dismantling of the economic systems that communities of color built in spite of this. And still, community development can perpetuate these effects, where the greatest proportion of benefits can inadvertently (or purposefully) flow to those who already have capital, never trickling down to those who need it the most, the very communities that policies purportedly are meant to support.

But community development can also expand our definition of wealth. What can happen when we acknowledge a more holistic set of assets in what we own and include past racialized harms in what we owe? Can we accumulate wealth, not only for the sake of reinvestment and lining the coffers, but to reinvest to foster a greater degree of shared power? When community development practitioners consider wealth beyond capital, what can that afford us in our collective ledger? What transformative power can community wealth building unlock for our neighborhoods when we ensure that everyone has the means to participate? Can we move beyond mere survival to genuine thriving?

The writers in this issue consider the tensions between leveraging a capitalist system that was only intended to work for white men, and the possibilities of building entirely new economic systems. They explore the opportunities and limitations of expanding homeownership as a wealth building vehicle. From guaranteed income to shared ownership models, they highlight models that prioritize sustainable community well-being, foster democratic control of assets, and strengthen resident power. Practitioners show that a more just economy isn’t just an idealistic fantasy, but a tangible reality within reach. Because money may not buy happiness, but it can invest in the conditions for health and well-being for everyone in our communities.

Onward.

Soni López-Chávez was born in Cuitzeo de Abasolo in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico. Pulling from her own Chichimeca heritage and lived experience as a first-generation immigrant, her art includes a wide variety of topics, including representing her Indigenous ancestry, highlighting her life lived between two nations, countering negative and preconceived stereotypes, and empowering historically marginalized communities.

If you search the Internet for the term “wealth building,” you’re likely to get a slew of websites from financial planners and other so-called experts who try to define for us what a prosperous life is and what one needs to do to achieve it. Save X amount of money each month, start an investment account by this age, acquire these assets – the list goes on. But all of this advice comes out of a framework that assumes wealth is simply defined as assets owned minus debts owed and that everyone’s top goal is to maximize their net worth as much as possible.

But when we asked Black mothers from Springboard to Opportunities – a nonprofit that works alongside residents living in federally subsidized housing in Jackson, Mississippi as they pursue their goals in school, work, and life – what they believed it meant to build wealth or live a prosperous life, they did not talk about asset accumulation or stock portfolios. They didn’t even talk about big houses or fancy cars. Instead, they described a life that was free from chronic stress and worry, where they have free time to spend with their children and invest in their own interests. They described being part of a safe and caring community, and paying all their bills with enough left over for savings and self-care or fun activities.

What our families described was a deeper and richer vision of prosperity than a typical wealth building framework – one that we have started calling holistic prosperity. Based in four interconnected and interdependent principles – Financial Stability, Time Autonomy, Dynamic Well-being, and Social Capital – this framework is grounded in the expertise and experience of low-income Black mothers and acknowledges that for a family to feel wealthy and believe they are living a prosperous life, it takes more than just cash and assets.

While a mother might be making enough income to feel financially stable, if she’s working 60 hours per week with no time for rest, her children, or her community, it does not feel like a prosperous life. Or if she is working reasonable hours but her pay is so low that she cannot afford the dues for her child to be on a sports team or play in the band, she still feels like she is coming up short.

Springboard is anchored in a belief that the families we serve know better than anyone else what they need to reach their goals and care for their own family, and they should be able to define for themselves what a whole and prosperous life looks like. Yet their voices and experiences are seldom considered when we create wealth building or even poverty-alleviation strategies. Instead, our policies and programs are grounded in false, deficit-based narratives that particularly surround Black women living in poverty and lead to paternalistic and punitive requirements that hinder a family’s ability to even build financial wealth, let alone the other aspects of holistic prosperity that our families have identified as essential aspects of thriving communities.

As we consider how to take a community-driven approach to wealth-building, we must start by examining the assumptions and beliefs we bring to the conversation. Too often, our programs and policies have left family voice out, and in doing so, have failed to create solutions that align with the needs or dreams of the people these solutions are meant to serve. But when we actually include families in the process and trust their expertise, we can create programs and policies that are grounded in dignity, equity, and trust and pursue their vision of holistic prosperity.

Sarah Stripp is the Director of Socioeconomic Well-being at Springboard to Opportunities, where she leads the organization’s cash-based initiatives and socioeconomic policy priorities. With more than a decade of experience in the nonprofit sector, she provides strategic direction and leadership, supporting families in reaching their goals.

I was just a little girl when I sat starry-eyed in front of a television screen watching Whitney Houston donned in a golden, glittery gown singing the words, “Impossible things are happening every day.” At the time, I was wide-eyed watching Black women be fairy godmothers, queens, and princesses, but – with time – those lyrics became a mantra for expanding my political imagination in a world hell-bent on limiting me. We accept crumbs from those with immense wealth and power, not because we don’t believe we deserve more, but because we have accepted “more” as impossible. But I am only able to write these words to you because those before me dared to dream of the impossible. At one point, it was impossible to imagine Black Americans unfettered by chains and free to own their time, labor, and bodies. That we would travel, not by force or in the hulls of ships, but to pristine and beautiful destinations purely for leisure. That Black people would be voting en masse and becoming elected officials. But people dared to make possible all of those “impossible” dreams. People who bent the walls that previously closed us in, who forced their way through doorways not previously available to us. Impossible things are happening every day.

Angela Davis once said, “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world and you have to do it all the time,” but unfortunately many of us have lost our way. We know that nearly 250 years of chattel slavery was unspeakable. We acknowledge the continued legacy of slavery and anti-Blackness that has led to racial wealth gaps, overpolicing, mass incarceration, redlining, and other thwarted opportunities for Black Americans. We recognize that America continues to be an unsafe place for Black people to be ambitious and free and joyful. But we don’t believe ourselves capable of changing that fact.

In the reparations movement, this is called “the hope gap,” the distance between the belief that reparations should be paid and that it will be paid. According to polling by Liberation Ventures, 70% of Black people believe reparations are needed yet only 7% of those supporters believe reparations are likely to happen in their lifetime. Hope is everything. The absence of it keeps us immobilized, resigned to accept what is being handed to us. But impossible things don’t happen accidentally. They are the product of deep belief, collective action, and insistence on changing our realities. We can’t achieve what we don’t believe or what we can’t envision.

So I’m saying that I believe. I believe in a world where Black families who lost homes and land through eminent domain will have it returned to them through local reversals. I believe in fair funding for our schools, non-profits, and hospitals. I believe in tax exemptions and reform, baby bonds, guaranteed income, and land grants. I believe in toppled Confederate statues and reclaimed plantations for healing and public education. I believe in community gardens where Black people of all ages can learn to grow their own food and tend to the land the way our elders and ancestors did. I believe in learning from and with our Native American siblings, proving that when Black and Indigenous people have land re-redistributed back to us, the planet thrives. I believe in Gullah Geechee not fighting for their islands, foods, and cultures. I believe in Native people thriving beyond reservations. I believe in sustainable fishing, hunting, and foraging that help us fall back in love with the country we built. I believe in no wildfires and more resilient coastal lands. I believe in fresh air not tainted by industrial plants and waste dumps. I believe in clean water for the Black children of Flint, Michigan and Jackson, Mississippi. I believe in Black land stewardship and communal wealth.

I believe in more than what “they” have led us to imagine as possible. I believe in turning the impossible into reality and then daring to dream of other impossible fantasies to tackle. I believe in never backing down from the opportunity to want and go after more because it is in our blood. I believe, and I hope you will too.

Brea Baker is a writer and activist whose book, ROOTED: The American Legacy of Land Theft & The Modern Movement for Black Land Ownership, details her family’s experiences across the South and pushes for reparations to include land distribution. With a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from Yale, Brea believes deeply in imagination and nuanced storytelling. She regularly contributes to ELLE and Refinery 29 Unbothered with other bylines in Harper’s BAZAAR, Oprah Daily, THEM, Coveteur, The Progressive, and more.

Growing up, I was captivated by “Choose Your Own Adventure” books – those narratives where you, reader, made decisions to determine the story’s outcome. Each single choice led to dramatically different endings.

Recently, I’ve been thinking about how those books mirror the reality of lower wealth owned businesses in America. For Black and brown business owners, available choices are often constrained by systemic barriers to capital. What if we could rewrite those stories?

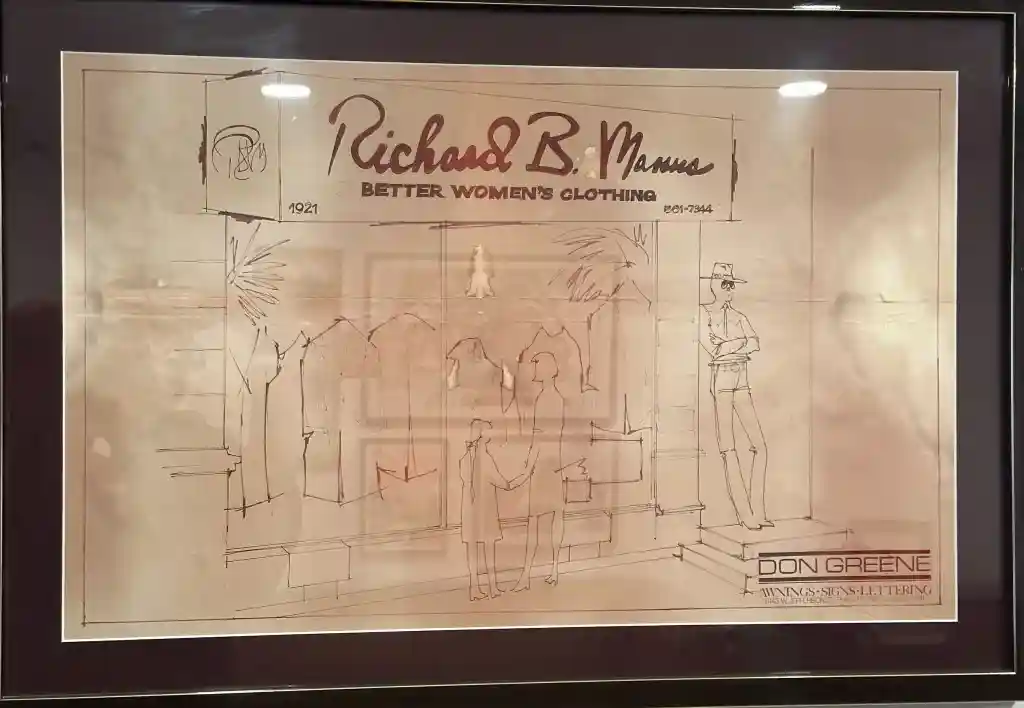

Let me tell you about my parents’ business through this lens, the story of Richard B. Manns The Clothier, and the two very different possible adventures.

You are Richard and Jacqui Manns, Black entrepreneurs in late 1970s Philadelphia. You’ve found the perfect location for your high-end women’s clothing boutique – the first floor of a historic mansion in prestigious Rittenhouse Square. You’re standing outside with lease papers in hand. But you face a choice:

Path A: The Traditional Route

You sign the lease. For fifteen years, you pour your heart into Richard B. Manns The Clothier, building a loyal clientele and working seven days a week, reinvesting every dollar back into inventory.

But by the late 1980s, the walls are closing in. Interest rates climb. Your rent keeps increasing – money flowing out of your family’s pocket into your landlord’s. You dream of expansion, of opening locations in New York and DC, of building something your children can inherit. You can sell a woman $1,000 in fine clothing in an hour – a skill that can’t be taught in business school. But banks don’t value your proven ability to move inventory or build customer loyalty. They want spreadsheets and proformas (most likely presented by a Penn Wharton graduate), not track records of retail success. Patient capital doesn’t exist in your universe.

The stress fractures your marriage. Late nights arguing about cash flow replace conversations about dreams. Eventually, you make the hardest decision: you close the store. You pivot to trunk shows, your business reduced to what fits in the back of a van.

Your children learn that even with talent, vision, and fifteen years of hard work, there are limits to what’s possible for families like yours.

The End.

Path B: The Access to Equity Capital Route

You sign the lease, but you’re not alone. A fund focused on wealth-building provides patient capital for you to purchase the entire building.

Everything changes. Instead of paying rent, you’re building equity. You convert the basement into additional retail space and rent out the upper floors. Your monthly costs plummet while your property appreciates. You’re not just running a business – you’re building wealth.

With this stability, you expand. Richard B. Manns The Clothier opens in Georgetown, then the Upper East Side. Your staff grows from two to twenty. You become known as business leaders and wealth-builders.

By the late 1980s, instead of fighting interest rate pressures, you’re leveraging your real estate equity for strategic investments. You develop a small chain of boutiques. You invest in other BIPOC-owned businesses. You become the patient capital provider you once needed.

Your children grow up seeing entrepreneurship as opportunity, not struggle. They attend college debt-free, their tuition paid from property appreciation. When they start businesses, you provide the seed capital no bank would offer you decades earlier.

Your grandchildren inherit not just money, but a mindset: that wealth-building is their birthright.

The End.

The Choice That Changes Everything

The difference between these stories isn’t talent, vision, or work ethic. It’s access to equitable capital that recognizes ALL entrepreneurs as wealth builders, not just service providers. When business owners transition from tenants to owners, they don’t just build individual wealth, they transform communities.

Today, organizations like Partners in Equity are rewriting these adventure stories. We provide the patient capital that enables lower-wealth entrepreneurs to purchase their commercial real estate, to build equity instead of paying rent, to create generational wealth instead of just surviving month to month.

The “Choose Your Own Adventure” books of my childhood always reminded readers that they could start over and make different choices. In real life, my parents didn’t get that luxury. But for today’s lower wealth entrepreneurs, equitable community development creates new possibilities, new paths, new endings to old stories.

The question isn’t whether these entrepreneurs have what it takes to build wealth. The question is whether we’ll provide the patient capital that makes wealth building possible.

Which adventure will you choose?

Talib Graves-Manns is a transformative leader and Aspen Institute Fellow reshaping entrepreneurship across America. Through Knox St. Studios, Partners in Equity, and Black Wall Street Homecoming, he has created an ecosystem connecting underserved entrepreneurs with capital, real estate ownership, education, and mentorship. At PIE, he co-founded a private equity fund providing down-payment assistance to help small business owners transition from tenants to property owners, building generational wealth and strengthening communities.

Across the country, communities are reclaiming control over land, housing, and commercial space – not just as a means of survival, but as a strategy for building wealth, stability, and belonging. From Baltimore to Denver to Philadelphia, local leaders are pioneering shared ownership models that keep value rooted in neighborhoods rather than extracted by outside investors.

These models may differ, but they share a common goal: shifting who controls and benefits from community assets. “Shared ownership” refers to collective ownership of land by a community or a group rather than by an individual or private entity. Shared ownership models are designed to ensure that the control and benefits of land use remain within the community, typically to promote affordable housing, preserve cultural heritage, support economic development, or provide communal spaces.

Community real estate ownership, the collective ownership of land by a community or group rather than by an individual or private entity, redirects wealth-building opportunities to people historically excluded from them. It anchors culture and connection in place. It ensures that development meets community needs, not just market demand.

And this work is growing.

We’re seeing a surge of new and expanded legacy efforts: community land trusts, housing and commercial co-ops, investment trusts, and hybrid models tailored to local context. These efforts aren’t fringe. They’re vital – and they’re forming the foundation of a movement.

But right now, that movement is still largely invisible, a set of unconnected dots across the national landscape.

Too many projects are working in isolation. Funders support innovation but overlook the long-term infrastructure the field needs. Policymakers see affordable housing, but don’t appreciate the ownership structures underneath. And many practitioners don’t yet see themselves as part of a shared ecosystem.

To help change that, the Center for Community Investment built the Community Real Estate Ownership Ecosystem Map – a new interactive tool that spotlights more than 200 community ownership efforts across the United States.

The map offers more than visibility. It offers possibility. It’s a step toward naming and resourcing this work as a cohesive field.

Because if we’re going to scale this work – not just in size, but in impact – we need to start treating it like the field it is. That means investing in the infrastructure: policies that support collective ownership, capital tools that align with community timelines, and narrative strategies that tell the full story of what’s working.

Shared ownership is one of the most promising strategies we have to confront racialized disinvestment, fight displacement, and build community wealth. But to fulfill that promise, we need coordination. We need connection. And we need to see these projects not as exceptions, but as evidence of a deeper shift already underway.

This is a call to connect the dots.

Explore the map. Share it. Add your project. Use it in grant proposals, policy campaigns, and resident meetings. Let it help us see ourselves as part of something bigger.

Gretchen Beesing is a seasoned leader in community economic development and the Principal of Yes/And Strategies, a consulting practice advancing community wealth and cooperative ownership. A Senior Fellow with the Center for Community Investment, she previously led Catalyst Miami, launching Florida’s first universal children’s savings program. With a background in social work and policy advocacy, she’s a frequent speaker and board member, recognized for her work in financial empowerment and community-controlled development.

Derek Abella is a Cuban-American illustrator and artist based in New York City who creates dream-like work for clients all over the world, big and small. His images have supported publications and brands such as The New York Times, The New Yorker, and Google. He is a graduate of the Pratt Institute.

For this trio of pieces, I decided to tap into the themes of community and nature. Even though we as a species challenge, reckon with, and even at times harm nature, we are still part of one big ecosystem just like all other living things. I wanted these pieces to represent building and nurturing a garden to show how powerful and beautiful it can be for all of humanity to come together. The colors and lighting I chose were meant to evoke joy and hope. Even when the world seems dull and dire, I think it’s nice to have a reminder that there is always room for us to grow, change, and support one another through recognizing that we are living one broad and shared experience.

We sat down with Adriana Abizadeh to discuss collective wealth building and neighborhood governance through a neighborhood trust.

I’d love for you to tell me a little bit about Kensington Corridor Trust (KCT).

Adriana: We purchase real estate on Kensington Avenue, a primary neighborhood commercial corridor, and we put it into a trust for the neighborhood to directly own, govern, and control. It is an anti-displacement, land conservation, and building preservation model. We produce permanently affordable housing and commercial spaces. The average annual household income in Kensington is about $26,000, which is less than half of the city’s. This is a neighborhood experiencing deep poverty, and historically has experienced abandonment. Over the last five years, we have decommodified 31 assets and have 10 small businesses in the collectively owned spaces. We’re proud that we have not lost a single commercial tenant, and we have had zero evictions to date.

So, how does it work?

Adriana: We are the nation’s first neighborhood trust, the only one focused on a commercial corridor. In addition to preserving real estate and producing permanently affordable housing, we are building a model for collective ownership. We looked at the best practices from community development corporations, which have done affordable housing and wraparound social service work for decades. Community land trusts, who decommodify land and buildings. Business improvement districts, who improve the built environment. Private developers, how they stack capital and move money quickly. We took learnings we liked, left behind the pieces we didn’t, and we built the neighborhood trust. We are a nonprofit that is legally and financially tethered to a perpetual purpose trust, which protects the land, buildings, and liquid assets for a particular purpose. The neighborhood defined our purpose – to preserve affordability intergenerationally and retain collective control of real estate in the commons.

I think that distinction between individual wealth building and collective wealth building is key. How are you thinking about how to build wealth in an anti-racist way?

Adriana: First, all things rooted in wealth building are rooted in racism. The fact that we all need to amass wealth in order to survive and sustain ourselves is a byproduct of a deeply racist system. Moving policy is critical to our work because we acknowledge the present is still determined by the same historic racist policies. We can say that redlining no longer exists, but the impact continues. You can clearly see very different health outcomes, employment, property valuations, proximity to environmental harm, and all of that follows those historic maps. At the KCT, we think about financial wealth, but we’re also looking at wealth as the built environment and health. Everybody wants to know our rate of return or how we recapitalize dollars. That matters, but when your zip code is tethered to your physical and mental health, we want to know how we move beyond those redlined barriers.

For us, collective wealth building is twofold. In capitalism, those who own the land amass the wealth and the power. So we build collective power for a neighborhood through the ownership and control of real estate. We want it to impact people daily, not just to build a portfolio. By keeping housing units permanently affordable, who might go back to school or access upward mobility?

The other aspect is wealth redistribution. Assets are collectively held, but that does not have to negate independent wealth building. We’re working on launching a community stewardship trust (CST), which will launch in 2026, replicating the model of The Guild in Atlanta. Folks will be able to make investments as low as $10 per month and receive healthy market rate yields while still preserving deep affordability in the housing. We’re operating in a way that is benefiting the collective and not rooted in traditional, racist standards.

That’s very exciting. Can’t wait to follow along. You said you’re five years in now. I’m curious to hear, what are some lessons that you’ve learned?

Adriana: First, we need deep value alignment with folks who stay committed to the vision when it gets hard. Because we’re working on systems, and it’s complex and heavy work.

Second, neighborhoods can govern themselves. When we transitioned to neighborhood governance in 2022, we heard externally that we would be missing key skills. But our board knows how Kensington feels, day in, day out. You can hire an attorney or an HR expert. You can’t hire for lived experience. And they bring a vast mix of expertise; the neighborhood is not devoid of brain power, so we were able to disprove those misperceptions.

We’ve learned to navigate in markets, have access to capital, and make rapid decisions. When I started, whenever a property would go for sale, I would have to beg our philanthropic and investment partners for a check. But we couldn’t move quickly enough, so we would lose buildings. As KCT built its reputation and portfolio, we now have cash on hand that allows us to move nimbly and compete with the rest of the market. We’ve had to learn to navigate this market like everybody else, but holding values and collective decision-making at the core.

One surprising lesson was that you can attract businesses to a historically disinvested corridor with high crime, vacancies, drug use, and sex trade. When we first started, we assumed we needed an 18-month vacancy in the commercial storefront for every proforma. We were so wrong. In less than six months, in 2022 we attracted our first business, and since then people keep coming to us. Why would you choose Kensington Avenue? Because it is home. 100% of the business owners either grew up in or currently live in Kensington. They know what it looked like before white flight and disinvestment, and they know what it has the capacity of being. It has been beautiful, organic, and has helped our finances.

This is a beautiful example of a place that a traditional risk assessment might have called too risky, but you’re actually experiencing a lower vacancy rate than would be expected anywhere. You mentioned your governance model. How do you collectively advance an equitable vision for the neighborhood?

Adriana: Our neighborhood governance began in 2022. At KCT, we believe the value of the neighborhood’s deep local expertise exceeds the external legal or HR expertise. Every January, we hold a neighborhood-wide call to let folks know about open seats. We give preference to folks who have been in the neighborhood for more than 10 years, since we know there is already active displacement. We hold two seats for folks under the age of 21, thinking about succession. We want to think about the next generation of leadership in a neighborhood that is changing and evolving.

It’s a blossoming model for local governance. We compensate folks for their time, because their time is valuable. Time is a social justice issue. They’re making decisions around what their neighborhood will look like into the future. That’s hard work that requires expertise and time.

We decided that the governing body’s 19 voices were not enough to represent 32,000 folks in the neighborhood. So we built larger feedback loops for people to tell us what properties to acquire, or what businesses to attract. The neighborhood approves every business, which takes time. But that has been critical to their success. People know they’re coming, want them to succeed, and patronize their businesses.

When I first came to KCT, people made it clear they wanted a grocery store. And this year, we’re launching a grocery store, owned and operated by a Kensington native. He’s been in the food import and distribution business for years. He approached us about doing a shared commercial kitchen, and we said we bought the property for a grocery store, but didn’t yet have an operator. He said, I’ll do both. And we couldn’t be more excited, because it was in direct response to what people wanted.

Governance has been a beautiful assembly of neighbors with different ideas. There is healthy discourse and dissent. It gets uncomfortable, and I love it, because that means we’re working together to make the best decisions for this neighborhood’s future. We’re really striving.

Adriana Abizadeh is the executive director of Philadelphia-based Kensington Corridor Trust (KCT), whose mission is to utilize collective ownership to direct investments that preserve culture and affordability while building neighborhood power and wealth. Adriana is also a policy fellow at Princeton University and Rutgers University. She has committed herself to serving on boards that reflect some of her deepest passions: immigration, racial and health equity, and youth development. When Adriana isn’t serving her community, she is at home with her husband, their four children, and two dogs.

We caught up with Ayonna Blue Donald to discuss the potential – and limitations – to homeownership as a tool for wealth building.

So first, I would love to start with you. Who are you and how did you come into this work?

Ayonna: I was born and raised in the inner city of Detroit, my mom still lives in my childhood home. I came to Cleveland for college, moved around, and when I moved back to Cleveland, I worked in the Building and Housing Department as a temporary employee. I was bit by the housing bug, eventually became the department director, and continued my career at Enterprise Community Partners about four years ago. Currently, I am the Vice President of the Ohio Market for Enterprise Community Partners, a national community development nonprofit, in the Solutions Division. We develop programs that meet markets where they are.

Tell me more about how the Make It Home program works.

Ayonna: Let’s start from the beginning. Rocket Community Fund had a similar program in Detroit and came to us interested in Cleveland’s state forfeiture process and how to leverage the Cuyahoga County Land Bank. In Detroit, they transferred properties to owners, but they still had to pay the back taxes. In Ohio, we have a state forfeiture process and strong land banking laws, and a potential homeowner can get the property without any tax liens or encumbrances. We thought this could be a great wealth generating tool. An occupant could own their home rather than a delinquent landlord who was not paying their taxes. We modeled the program to suit Cleveland specifically. We’ve thought a lot about the needs of potential homeowners and partnerships in this program.

We are a legacy city. Most of our housing stock was built before 1950, almost 100 years old, and not in great condition. We are leveraging several funding sources, including American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) dollars to deliver home repair grants. Becoming a home owner of a home that needs thousands of dollars of home repair, would not be the same wealth building opportunity that we intended

We also included financial counseling and homeownership counseling for all prospective owners. We wanted people to be equipped financially for the responsibilities of owning a home and be able to sustain it. When your garbage disposal doesn’t work or your roof leaks, you have to fix that. Most people don’t have discretionary funds for those unexpected repairs. We didn’t want to set people up for financial ruin, so the program helps people prepare for these hurdles.

When I was at Building and Housing, I found that properties would sit vacant when someone dies. Either the family doesn’t want to go through probate, there is no will, there are multifamily members to negotiate the outcome of the property, etc.. But if you leave the property to someone with a survivorship deed, it doesn’t have to go through probate. You can automatically transfer that property to the intended beneficiary at that one owner’s request. We purposefully partnered with The Legal Aid Society, to provide legal services to our new homeowners, to be able to protect their asset, for a generational wealth building opportunity.

You really incorporated holistic scaffolding for the program. So you wanted to reach 50 new homeowners. How is it going so far?

Ayonna: We are working through a pipeline of interested homeowners. But sometimes it is hard because the program sounds too good to be true, when we’re offering thousands of dollars in support. Most of these properties are in redlined communities, and there’s a trauma response after seeing so many unfulfilled promises. One of our new homeowners said she prayed every Sunday that this was true, because so many bills of goods did not get delivered. We have outreach workers on our team who knock on the doors to have conversations with people, but it’s still amazing how many people are skeptical of the resources.

We also know not everyone is going to be a good fit. Some people are not interested in homeownership, because not everybody wants to be a property owner, or do not see the value of owning that home in Cleveland.

What does wealth and wealth building mean to you?

Ayonna: It’s important to recognize that building wealth means something different to a lot of people. For me, wealth is the ability to pass something on to someone else. You can have a wealth of wisdom or resources. It does not have to be cash in your bank account. Community development is knowing the value of the wealth of your community, what you have to give and offer to others. It could be your proximity to the lake or to public transportation. What is that special thing that you’re sitting on? A home is just one form of wealth that you can pass on as a legacy to your children. We all have wealth; we just have to figure out what that is.

In its best sense, how do you see homeownership as a tool for wealth building, and how does that impact equitable community development?

Ayonna: When you have stable housing, then you have a stable community. One thing that we share across humanity is that we all need somewhere to live. Even if the conditions are not good or permanent, you still lay your head somewhere. We can’t build a community without people, and those people need somewhere to stay.

Even though it may be against the law, people still exclude renters based on race, class, or source of income. On the policy and advocacy side of our work, I heard from one person re-entering society that they had been home for 20 years, but still could not apply for an apartment because they had to check the box, and their involvement with the criminal legal system excluded them from renting. Homeownership is a bit different. When somebody else owns your home, they control you. Having ownership gives you control. There’s power behind that.

Ultimately, the homeownership rate for Black families across our city is about 35% and for white families it is over 70%. It’s just basic math. You extrapolate across our country and see a large disparity in net worth too. Knowing that disparity, owning a home is a great start to wealth building in our country.

Ayonna Blue Donald leads Enterprise’s work across Ohio, advancing housing-based programs and creative policy solutions that help Ohioans achieve housing stability and economic mobility. A longtime public servant, Ayonna served as director of the city of Cleveland’s Department of Building and Housing and the chief of Commercial Services and Governmental Affairs for the Department of Port Control.